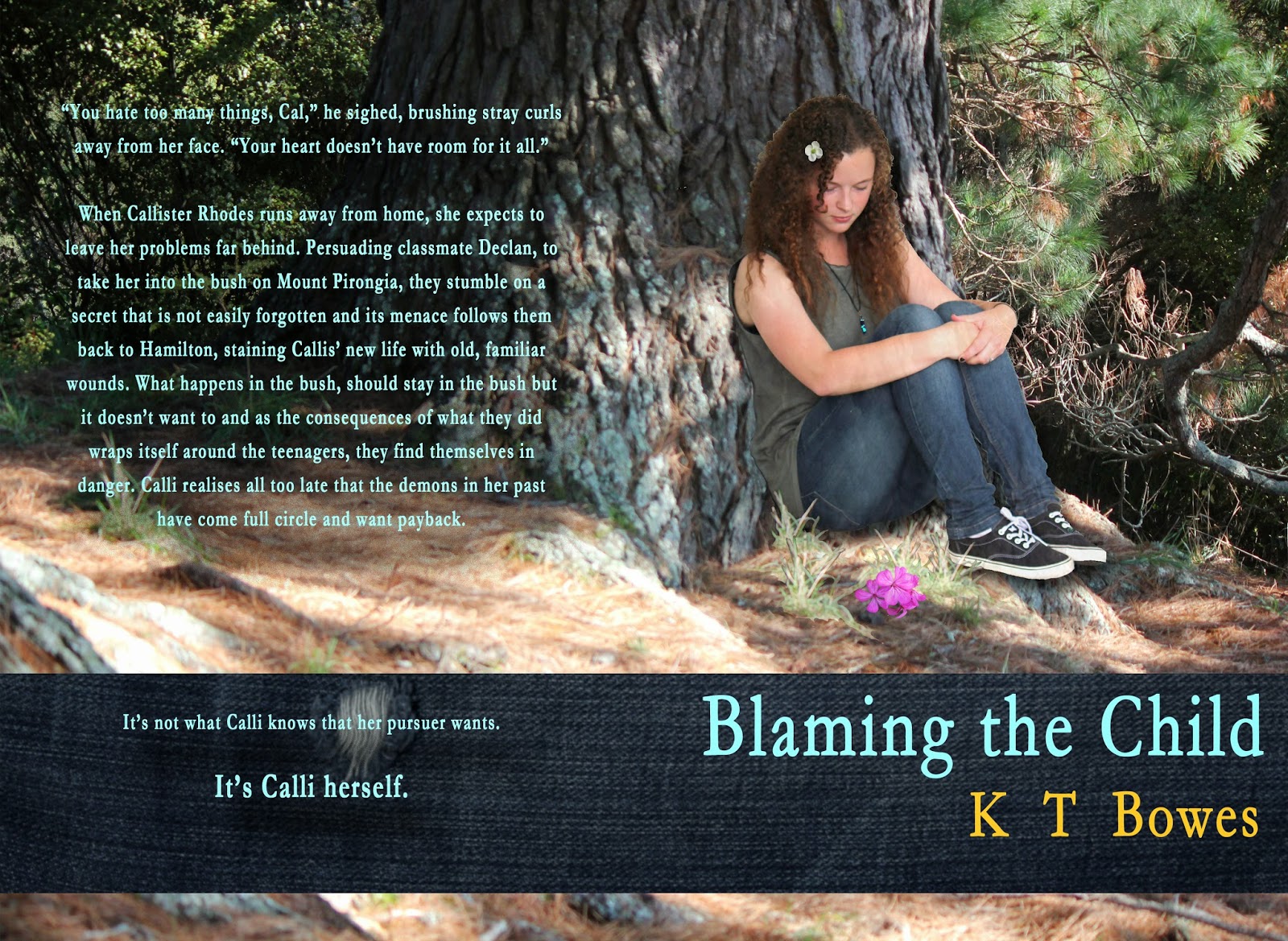

Blaming the Child seemed like an apt title for a novel in which the child was held responsible for the actions of adults, who should have known better. The storyline is complex, involving a teenager who unknowingly shoulders that responsibility and tries to make a decent life beneath its suffocating burden. When Callister Rhodes really can’t take anymore, she uses the only exit she can see and runs away, ending up in foster care and fractured from her family completely. The irony is that she should never have carried that weight. The responsibility for her parents’ failings was not hers. She did nothing wrong.

Calli’s circumstances are extreme, but I got to thinking this week about how many of us force responsibility on our own children for things they should never carry. We bring all this baggage into our relationships and parenting that really have no right to be there. We carry forward the mistakes of our parents, our own inadequacies and the burdens placed on us. And we make them responsible.

I

knew a woman whose children did every club under the sun. If they weren’t

swimming they were playing soccer, tennis, rugby, dancing and piano, singing or

performing in a gymnastics competition. They were bright, clever children, but

they groaned under the weight of activity and busyness. From the outside, they

looked ‘favoured’ and fortunate. My children would have loved to do half those

things and looked enviously at them as they were slung into the car after

school, half dressed for the next activity. My children were allowed to pick

one activity each, for as long as it lasted. It was this or that. We had no money so they could do school soccer because it

was free and the uniform came with team membership and then learn to play

guitar at a reduced rate with a neighbour down the road, in exchange for childcare.

Playing with bubbles in Grandma's garden in England

I

remember my daughter inviting one of the children-who-did-everything

round for a play-date once. They did homework at the dining table for half an

hour, ran round the garden in the snow, had tea and then flopped in front of

the fire and made things with salt dough until it was home time.

I

felt inadequate, as though my entertainment was pretty dire compared to what

the five-year-old usually did after school and I worried terribly about it. I

hovered like a nervous blowfly, watching for signs of boredom. After the

frantic mother had yanked the child from my threshold and rushed off to the

next activity, I asked my daughter if her friend had enjoyed herself. I got the

usual shrug and noncommittal ‘yep’ which told me nothing. But every day for the

next two weeks that little girl ran up to me and asked if she could come back

to mine and sit by the fire. Sadly we never managed to fit it in again.

In

our own way, as mothers, possibly both of us were punishing ourselves and our

children, but in different ways. I made my children count the cost of

everything and she was probably the opposite. Maybe she had grown up poor with

nothing and wanted to give her children everything. I grew up poor but had what

my family could provide and if I’m honest, I remember tantrums and arguments

because I wanted more.

|

| Dingley Woods, Northamptonshire.We spent hours here. Photo courtesy of Tracey Rawlins, my friend in England whom I miss very much. |

With

my own children, I did free stuff; bike rides and bus rides and trips to the

park. But I placed a massive burden on myself without meaning to. I had four

children. I loved and wanted them all. But it made playdates where the whole

family was invited highly unlikely. One or two extras, maybe - but four, no

thanks. My burden was not to let my children ever miss out because there were

more of them than in other families. My theory was that they didn’t ask to be

born and so shouldn’t be made to suffer for mine and my husband’s choices. So

we did stuff.

I put pressure on myself to fill at least three days a week in

every summer holiday. With no money.

My children were grateful, walking around the reservoir and not going into a

cafe for ice-cream after. When I look back, I am amazingly gratified to them

for not asking for things. But I always worried that I didn’t quite do enough

and so I punished myself and inadvertently, them.

In

order to fund our growing family, my husband worked long hours away from home,

weeks and months at a time, maybe popping home late to sleep. Effectively I

single-parented for a number of years, plugging into things to stop the

children feeling the absence of a male role model. They didn’t need it. They

knew dad loved them and worked hard for them. They didn’t need my futile

overcompensation on their behalf. It was my problem, not theirs.

I

made my own nightmare, second guessing and spinning on my head to make this

complicated image of the perfect family

work, whilst knowing deep down that it was never going to.

And who did I get cross at when I

was tired? When I had cycled miles with four wobbly

little people on stabilisers, shoved my fat backside down the slide at the play-park

for hours and couldn’t get the play dough out of my hair?

And who did I get cross at when I

was tired? When I had cycled miles with four wobbly

little people on stabilisers, shoved my fat backside down the slide at the play-park

for hours and couldn’t get the play dough out of my hair?

I

was cross with them, the children.

The

same children who would probably have been just as happy at home in front of

the fire watching cartoons, playing with toys or digging a random hole in the garden

with the dog.

A friend's birthday party. One of our few NZ family photographs.

The

grass is always greener on the other side.

Whether

we have everything or nothing, we need to learn to make do and smile through

it. Ultimately, that’s what our children are looking for; for us to be content

with what we have. That’s their

benchmark. In our more affluent times as the better jobs came and the bigger

houses, surprisingly it’s not what my semi-adult children remember. They don’t

remember dinners out or fancy toys or trips. They remember me reading Harry

Potter for a solid week on a wet week in Mid-Wales with the gas fire pumping

out dry heat, me losing my voice and the rain smashing into the side of the

caravan. They talk with fondness and excitement about coming to New Zealand

with just a suitcase each and travelling the North Island in a campervan with

no home, no jobs and no idea of what was coming next.

They don’t think like we imagine

they do and - we get it wrong continually.

I

was fortunate. I had good parents. My mother cycled miles every Saturday to

take my sister and I horse riding and then cycled home because there was

nowhere to wait in the biting cold. Then she cycled back again. I appreciate it

now, but at the time it was my birthright.

I look back and feel like a brat. She worked two part-time jobs to fund that

hobby and all me and my sister did was bitch and argue all the whole way home

about who got to ride out front. My mum grew up with nothing and wanted us to

have the world and on and on it goes.

My wonderful parents arriving in NZ after 3 years apart.

In

Blaming the Child, Calli’s home

circumstances are different. Both her parents work full-time and she is the

unpaid child-minder, housekeeper and problem solver. They don’t need two

full-time incomes, but it's the adult's way of avoiding home. It dawns on Calli at

the tender age of sixteen that her mum and dad don’t seem to love her like they

do her younger siblings. She tries to find out why and her life blows up in her

face. Her parents have carried their burden forward and laid it firmly on her

shoulders and it is truly horrific. The great irony is that for sixteen years

she has been aware of a weight that she didn’t even need to know about, let alone carry. It’s theirs, not hers.

We

all do it. We don’t mean to, we didn’t intend to, but we do.

Parents,

take a good hard look at your parenting.

-

Why do your children do more activities than days of the week? Is it because

they want to be accomplished, or because you want them to?

-

Don’t tell your children that you can’t

afford things. If you or your partner are working to provide for them, then

don’t demean your stellar efforts. You are doing the best you can. Tell them

that you have considered their request and decided that it is not a priority at

the moment within the other demands on your time or money. They won’t die.

-

Most of our parents did the best they could with what they had in their hand at

that moment. Some did great and some did appallingly. We cannot redress the

balance of their mistakes in us by overcompensating in our own children. Wipe

the slate clean and start again. We always declare boldly that we are going to

do it differently, but few of us manage to strike a healthy balance between extremes,

on our selfish mission to be better.

-

Much like beauty, success is measured by results and usually by the beholder - who is your child. They never like their

lives. So don’t ask. They always have some major and life-changing

complaint so don’t listen to them in order to form an accurate assessment of

how you’re doing. Look at the world around you. If your children are fed,

clothed, taken care of and told they are loved, then you are doing ok.

My husband and son, soccer referees together a few years ago.

At the end of the day, you are family. The Maori word is whanau. Some days we do our best and other days our worst. Life is hard enough out there. Don't bring it home.

| I painted this. It hangs in our family room as a reminder of who we are. |